The gentility of the bourgeois boudoir and boardroom to the realpolitik ‘on the ground’ has been the four-decade long journey of South Africa’s most significant and globally capped visual artist, William Kentridge.

While so much of the focus of the dual retrospective exhibitions, Why Should I Hesitate: Putting Drawings to Work, and Why Should I Hesitate: Sculpture, which opened in Cape Town at the Zeitz MOCAA and Norval Foundation this past weekend, has been on art as art-making process, it is also in the searing social commentary and its artistic formulation that William Kentridge’s genius lies. Significantly, it was born from the fertile soils of apartheid South Africa.

While the art world across every continent has luxuriated in expansive exhibitions and monumental installations of the artist, we have had to wait for decades for Kentridge to share his prodigious oeuvre with us, in what are said to be the largest retrospective exhibitions to date. (Kentridge has enjoyed the honour of many “career surveys” in the past.) Kentridge, the cultural commentator, and his full team of collaborators, have unfurled on us, the gallery-attending public, a massive oeuvre.

Emanating from the violent despotism of 1970s and 1980s South Africa – and onwards over four decades, and many more countries, Kentridge has soared and flourished, amassed global acclaim and brought in more and more collaborators on larger commissions. From art/apartheid reality he provided macroscopic commentaries encompassing art and cultural history, ideologies, political depravity – colonial, post-colonial and contemporary histories and realities – Ethiopia, Istanbul, and, most recently, Lampedusa, southern Italy.

But, most significantly, the exhibition at the Zeitz MOCAA has thrust us back to the poignant familiarity of the dark, pain-filled 1980s, where it was left to artists to tell the truth about our regime in metaphors.

The 1980s and beyond

During the 1980s, the artists and cultural workers were often the sole voices of the voiceless. As weekdays rolled out in teargas-choking hazes and staccato, deafening gunshots, and weekends echoed with the dirge of mass funerals, the theatres and galleries became the gathering halls, the centres of truth and realpolitik.

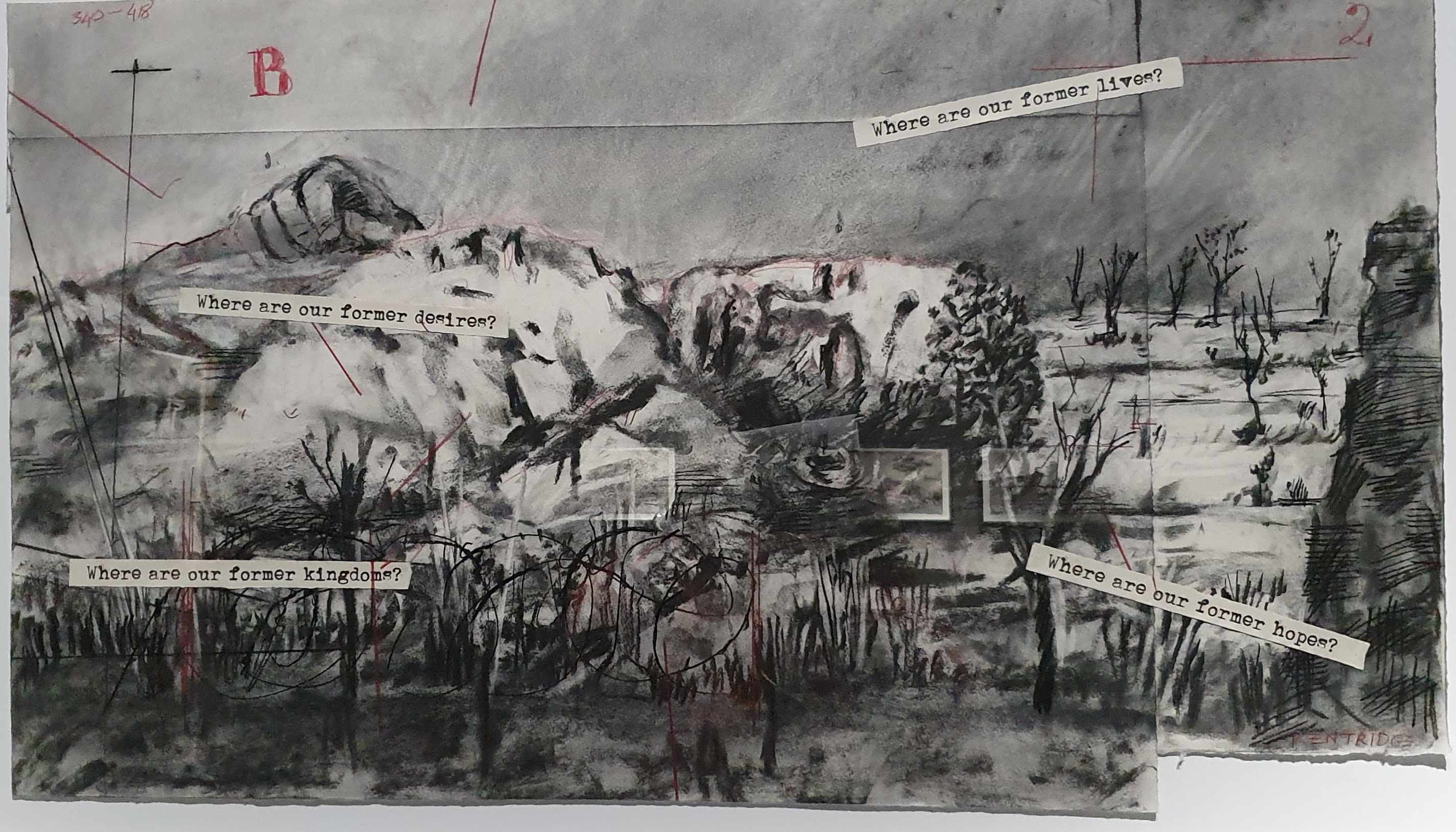

It was at this time that Kentridge’s seminal works roared into the spotlight in protest against the chaotic, censored battlefields that defined our socio-political landscape. The artist’s award-winning triptych for the South African Triennial The Conservationist’s Ball (not on show at the Zeitz MOCAA, but which shares the same context as Luncheon of the Boating Party, 1985), was a searing dark satire borrowing from the German Expressionists — Otto Dix, George Grosz: The bloated white oppressors greedily filling their bellies at a teeming banquet while, all around them, the post-apocalyptic landscape was exploding and self-destructing. This monochromatic triptych in charcoal (with a touch of blue) cemented the Kentridge visual lexicon into our aesthetic discourse: The Highveld landscape; the hyenas feasting off the decaying city carcasses; the detritus of colonial and apartheid excess.

Shortly thereafter came the agonisingly cruel and ironic Casspirs Full of Love, (1989) (on the exhibition, in Room 1). It was created at the height of the state of emergency, when those ubiquitous “mellow yellows” — military vehicles filled with young white servicemen — were dispatched into the barricaded townships to enforce “law and order” for the regime.

The stark, longitudinal, claustrophobic, monochromatic charcoal work depicts disembodied heads crammed into those airtight vehicles propelling forward to deliver domestic warfare (for visitors to the Apartheid Museum, one work from this series is placed alongside a real mellow yellow) and preceding the disembodied genocides that came to Rwanda and Bosnia barely half a decade later. At the time, they were exhibited contrapuntally alongside azure gouache irises, a trope he returns to regularly to give the viewer a break from the inhumane – and forming a soothing break in an installation “study” created in the Zeitz exhibition.

Back then, Kentridge, son of the legal brain, Sir Sydney Kentridge, QC, had graduated in politics and African studies and completed a diploma in fine art at the studio of legendary artist and cultural activist Bill Ainsley in the 1970s (where Helen Sibidi, David Koloane, Sam Nhlengethwa, and other great South African artists were wielding brushes and chalks) and moved on to study mime at Ecole Jacques Lecoq in Paris, in 1982.

On his return, he began to dabble in both theatre and art, with the Junction Avenue Theatre Company. A theatre company nestled in the Parktown Ridge, Johannesburg, it served as home and refuge for a multiracial company that lived and worked together in contravention of apartheid laws (other such groups drew together into collectives in Crown Mines and Yeoville — creative output included silkscreened posters inciting social revolution).

At a time when the dominant discourse of the oppositional and progressive intellectual groups incorporated a devotion to Marxist practice, Junction Avenue practised and espoused the revolutionary ideologies of the Russian Constructivists, German Expressionists, Bertolt Brecht and others. Kentridge moved smoothly between theatre and fine art, puppetry and performing, as seen through his iconic poster-making — on massive brown paper sheets. (See the silkscreens on the exhibition: Art in a State of Grace, Hope and Siege, 1988.) It was at that time that Kentridge began to transpose the malleable images from his charcoal drawings into his uniquely-honed animated filmmaking. He had indeed found his métier.

While, over the years, he has experimented in a diverse range of technologies and media, his dominant messaging has focused on social and political excess and inequities, art historical and art biographical meta-textural symbolism and technological innovation where verbal and visual metaphors morphed wittily into visual games, or expanded into massive installations.

As his fame soared, Kentridge took his team with him – collaborating for more than 25 years with SA composer Philip Miller whose hauntingly synesthetic evocations of Africa and classical music underpin most of Kentridge’s multimedia work, and with video editor Catherine Meyburg.

With each year, the artist’s narrative and medium grew and changed – whether located in South Africa, or commissioned in Germany, Italy or Istanbul. They were all centres of history, centres of oppression, seats of class struggle and often ripe for a new historical inversion. Over the years, retrospectives came and went; particularly haunting was the exhibition of 2002 that travelled from the New Museum in New York, to the Chicago Museum of Contemporary Art and showed at the South African National Gallery in a slightly truncated form.

Today, Kentridge’s work is displayed in two venues – although the artist indicates it is only 10% of his oeuvre. While the Norval Foundation has focused on a tightly curated exhibition of Kentridge’s sculpture (curated by the lead curator, artist Karel Nel with the Norval and Kentridge team); the Zeitz MOCAA has devoted three floors of the building to a generously constructed multimedia retrospective, carving out walls to accommodate entire installations, curated by former interim director and chief curator Azu Nwagbogu and Tammy Langtry, again in collaboration with the Kentridge studio of artists and specialists.

The Zeitz MOCAA exhibition chronologically

Beginning on the third floor of the museum with Room 1, is the chronologically- and thematically-curated multimedia exhibition. The 1980s pass far too quickly in that tight space and include Art in a State of Grace, Hope and Siege; Luncheon of the Boating Party; Casspirs Full of Love, which, I — perhaps erroneously — recall was borrowed by Kentridge from a sign-off on one of those Forces Favourites radio programmes, beaming to “our boys on the border”, plus an early Procession piece – Arc (1990).

Room 1 leads on to an intimate hallway devoted to Little Morals (1991) — petite prints, portentously depicting the political process of our transition to democracy. The morals remain pertinent to this day.

It is in the work of Ubu and the Truth Commission, written by Jane Taylor in 1997, and performed with the Handspring Puppet Company, that the absurd symbol of Alfred Jarry’s Ubu Roi first appears and is translocated into South Africa.

The video installation builds on Kentridge’s animated film oeuvre of that era (installed on the ground floor of the museum). Intimate, social, and brutally funny, the series of animated films started with the fictitious duo the Mining Magnates, Soho Eckstein and his alter ego, Felix Teitlebaum, inflated and importantly counting their riches, while the miners work ceaselessly creating the wealth as well as forming a revolutionary mobile social geographic landscape for the mining.

At the time of this body of work, Kentridge was living in Doornfontein, Johannesburg, where the sounds and sights of the city — workers warming themselves on metal braziers in winter — provided inspiration for these early films and theatre tableaux, with soundtracks punctuated with the operatic cries of a disposable working class whose diurnal lives provided a choral backdrop to their daily work.

Where Athol Fugard’s Boesman instructs Lena to “put your life on your head and walk”, Kentridge’s Brechtian Joburg proletariat trudge resignedly onward with the burden of their lives – their life possessions and demarcation of station – atop their heads, an infinite circular march, held in static heroic pose by the massive sculpture co-constructed with Gerhard Marx – Fire Walker (2009) – that towers 11m high over the taxi rank as one enters downtown Joburg from the Queen Elizabeth Bridge.

The proletariat procession is a recurring refrain. In his recent work The Head and the Load (2018), which celebrates a lacuna in history, the fallen black heroes of World War 1 – the carriers of provisions for the “real soldiers” – the procession continues. More than one million Africans died in the war to end all wars. The original maquette for the final 55m-long stage piece for 40 performers is reconstructed here as a video installation, KABOOM! accompanied, again, by music created by Philip Miller. The stark insight comes from a triptych of drawings which form the base for the final images for the moving tableau. Here lie fallen heroes — their corpses disembodied and reminiscent of Casspirs Full of Love.

It is in Room 5, with Il Sole 24 Ore and What Will Come (Has Already Come) (2007) that Kentridge creates what, for this viewer, has always been one of the most sublime commentaries on politics and war, and the devastation suffered by ordinary people. An utterly exquisite tabletop projection that holds the viewer enrapt in the beauty of design forms a visual roundabout for a horrific, animated film on the devastation of colonial wars on the East African people, using Eritrean folk songs countered by the politesse of Shostakovich. It places the viewer in the playground of gross war – the invasion of Ethiopia by Italy in 1935 – where 275,000 Ethiopians lost their lives. But it could be Syria 2015, or Yemen 2019.

Then Kentridge’s gaze turns to contemporary colonialism — Chinese African colonialism. The colonialism of extraction, imposition and excision of indigenous culture: two portraits of Chairman and Madame Mao rendered on “found” literary paper (Chinese script) accompany a massive three-screen video installation, Notes Towards a Model Opera (2011) where Chinese agitprop images and anthems intercut with Dada Masilo dancing with a red flag — on pointe.

For those who were not privy to the 2015 installation for the Istanbul Biennale, O Sentimental Machine exploits Kentridge’s fascination with mechanical sound machines. Parody and wit abound in a surreal and Dadaesque installation depicting Trotsky and his devoted secretary, played by artist Sue Pam Grant. Based on an incident when Trotsky, in exile, had moved to an island outside of Istanbul, Kentridge reconstructed the Hotel Splendid where Trotsky stayed. The “Sentimental Machine” is Kentridge’s recurring symbol for autocratic persecution — the megaphone a recurring synecdoche for power. The autonomy of the object is repeated regularly not only here, but in the sculpture exhibition where mechanical sculptures come to life in a constructivist cacophony.

But it is in the comfort of the print studio downstairs that Kentridge’s punch to the solar plexus lands. Gently couched as a discussion on technique, the gallery almost allows meaning to be overridden by the process. Commissioned to do a 550m frieze, Triumphs and Laments, on the banks of the Tiber in Rome in 2016, Kentridge scanned centuries of Italian history, from Garibaldi onward. While he could have been tempted by Italy’s history of fascism as one flamboyant artifice, his gaze landed squarely on the little island of Lampedusa.

The formerly idyllic holiday island which African migrants now treat as their entry point to a new life becomes the placeholder for his procession. Images of boats, refugees with their possessions on their heads grace the walls. The exhibition guide notes that the commissioned frieze etched into polluted layers will disappear with time, covered over by “fresh” pollution. Thus, only the source etchings and artworks will remain after the frieze is eroded by pollution. And, indeed, that is his primary message: transience, time, transmutation, and the cruelty of history and power in the wrong hands; as well as the converse: the dignity of poverty and the ordinary person; a passing procession, soon to be erased once more.

Or not: As the unsuspecting viewer looks up from the printer’s plate, placed to explain the collaborative art-making process, a drawing on the wall, a bold monochrome graffiti, a frieze, morphs into a metal rebus sculpture. The ‘drawing’ on the wall is made from steel and is the indelible image of the three-year-old Syrian refugee Alan Kurdi, whose lifeless body was washed up onto a Turkish beach in 2015 and digitally transmitted across the world.

There is no relief as the viewer heads into the final hall. More Sweetly Play the Dance (2015), the mammoth multi-screen video installation staged for the opening of the Zeitz MOCAA, is now expanded to its original size. With the iconic megaphones in hand, the procession of the walking dead passes before us, wheeling medical drips – history in the making (the Ebola epidemic). Again, this work hearkens back to the 1980s – circularly evoking the infinite procession depicted in the films and theatre in the 1980s where Kentridge used the haunting melodies of African choral syncopation as political commentary. And on to the procession of the Great War, the marching dead, the lines of migrants; endless echoes of repetitive Holocausts, a bleak recurring refrain of migration from and to political oppression.

In a sleight of aesthetic transformation, the Zeitz exhibition Putting Drawings to Work closes off with a hall filled with Stephens’ massive tapestries — woollen testimonies to Kentridge’s sweeping history, concluding with the most recent 2019 work, And When He Returned.

Norval sculpture: a postscript

The technical mastery – from charcoal, to animated charcoal video, to opera and theatre, to bronze and wool and technological innovations — is just one facet of the prolific maestro’s work, and his collaboration with master artists and artisans.

The reformulation of concept and line into three-dimensional form is picked up at the Norval Foundation and focuses on Kentridge’s “unsuspectingly emerged as one of the most innovative sculptors in South Africa and internationally”. The exhibition directs the viewer through hallways of technical mastery – from the first bronzes in collaboration with sculptor Neels Coetzee in the 1980s to the collaboration with Gerhard Marx for the iconic Fire Walker and on to the Russian constructivist self-automated “perfect machines”.

The Renaissance also plays out with the visual Rebuses that transform in space, from abstract shapes to visual double entendres. In this meticulously curated exhibition, the final room is uplifting as Kentridge takes a massive leap forward into solidly modernist bronze – transforming his own tropes into huge 3.5m-high bronze sculptures. ML